Gay Life in Berlin Is Starting to Echo a Darker Era

The right-wing resurgence in Germany recalls prewar Berlin. It may signal an ominous turn for the country’s gay community.

Updated at 9:30 a.m. ET on March 12, 2019.

BERLIN—The fetish cruising bar Bull is a place of pilgrimage in Berlin for more than one reason. To patrons, it is a 24-hour safe space that caters to every palate. To the British historian Brendan Nash, it is a symbol of “Babylon Berlin,” a golden decade of LGBT freedom in the city in the 1920s, when the bisexual Hollywood star Marlene Dietrich mixed with prostitutes and transgender dance-hall girls.

“There’s been a gay bar of some kind at this address for more than 100 years,” Nash, an energetic 54-year-old, explained to a walking tour he was leading as he gestured enthusiastically at a neon sign outside, which featured cattle with large nose rings. Chuckling, he told the group that an elderly woman nonchalantly wanders through Bull with a sandwich cart at 5 a.m. in case anyone is hungry. “There is nothing that she has not seen,” he said.

Germany has long been lauded for its liberal attitude toward sex. It recently passed laws allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt, and just became the first European country to legalize a third gender. But LGBT-rights groups have warned of a parallel rise of violent homophobia in mainstream politics.

Since the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) Party stormed into the Bundestag last year, its politicians have called for homosexuals to be imprisoned, vowed to repeal gay marriage, and denounced those suffering from HIV. Such attacks not only symbolize yet another seismic, global shift to the right. They are also reminders of Germany’s fascist past and, rights groups worry, signs of dangerous future clamp-downs on vulnerable minorities.

Berlin is a powerfully queer place—gay culture, politics, activism, clubs, and sex reverberate through the city. Crowds here dance under confetti rain at annual Christopher Street Day, or gay pride, parades. A fierce campaign is under way to protect intersex children from surgery, and antiracism protesters regularly drown out far-right rallies. But “Germany is not the shiny, progressive country it wishes to be portrayed as,” says Katrin Hugendubel, the advocacy director of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association in Europe (ILGA-Europe), which represents more than 1,000 LGBT organizations.

In 1918, when Bull’s predecessor first opened, Weimar-era Germany was embarking on a scandalous decade. Gay communities in New York, Paris, and London faced the threat of imprisonment, financial ruin, murder, or even execution. Berlin’s reputation for wild immorality and its unusually liberal law enforcement, by contrast, helped turn the city into Europe’s undisputed gay mecca.

By the 1920s, Berlin was home to an estimated 85,000 lesbians, a thriving gay-media scene, and around 100 LGBT bars and clubs, where artists and writers mixed with cross-dressing call girls who supposedly inspired the Some Like It Hot director Billy Wilder. Magnus Hirschfeld’s revolutionary Institute for Sexual Science openly lobbied for the decriminalization of homosexuality and helped transgender men apply with government agencies to live legally under their new gender. Audiences, straight and gay, queued up at Eldorado, a Jewish-owned nightclub where trans women and drag queens performed and gave paid dances to visitors. There, patrons watched the drug-addled, bisexual Anita Berber star in naked dances named after narcotics. In 1929, the British writer Christopher Isherwood, whose pivotal years in Berlin were brought to life in the film Cabaret, wrote in his diary: “I’m looking for my homeland and I have come to find out if this is it.”

Isherwood is something of a passion for Brendan Nash. With a shaved head, a hooded jacket, and an endless supply of racy anecdotes, Nash is not your average armchair academic. For the past eight years, he has transported tourists and earnest gender-theory students back in time to search for the ghosts of their pioneering heroes, as part of his popular LGBT walking tour around West Berlin’s “gayborhood” of Schöneberg.

But lately, the tour has taken on a different meaning. Instead of merely teaching history, he’s drawing parallels with the present.

“1932 was the 2016 of its age,” Nash explained to a rapt group, muffled in thick coats in the bright, cold sunshine. Passing around a 90-year-old one million Deutsche Mark note—a legacy of the period’s hyperinflation, which drove many people to embrace populist politicians—that he had found at a flea market, he added: “Desperate people in poverty were being promised jobs, that they could ‘take back control’ and ‘make Germany great again.’”

The electorate voted, and the National Socialist German Workers' Party, which would become the Nazi Party, in November 1932 won the largest share of the vote, taking up 196 seats in the Bundestag, a shocking result for a group that had garnered less than 3 percent of ballots just four years earlier.*

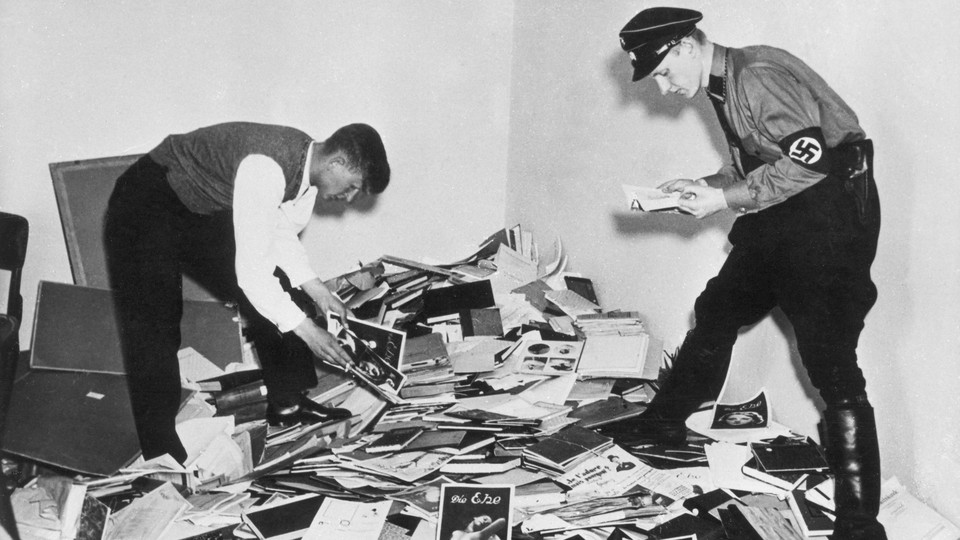

On May 6, 1933, the Institute for Sexual Science was looted and same-sex dancing was banned. From 1933 to 1945, an estimated 100,000 LGBT individuals were arrested. An extraordinary decade of sexual freedom was over.

Nash talked ardently of the comparisons between the rise of fascism in the 1920s and 1930s and modern German rhetoric. “When I read political speeches from 1932, I think to myself, I heard someone say that on the six o’clock news last night,” he said.

The current political mood in Germany is unstable, with old fractures reopening between the conservative East and affluent West. In September 2017, the AfD made history when it became the first overtly far-right party to sit in the Bundestag in 60 years. Founded in 2013 as a fringe, anti-migrant group with alleged neo-Nazi links, it is now the third-largest party, with 92 seats in the Bundestag and a representative in every state.

Since the AfD’s arrival, the LGBT community has experienced “unbearable incitement of hatred,” says Micha Schulze, the managing editor of the LGBT news site queer.de. He cites AfD politicians calling same-sex marriage a “national death” and posting an obituary on their website mourning “the German family.” Reported hate crimes against LGBT individuals in Germany rose by roughly 27 percent in 2017, according to the German Interior Ministry—a figure that Schulze and other LGBT groups claim is “the tip of the iceberg.”

In October, the AfD co-leader Alexander Gauland, who has vowed to repeal same-sex marriage, was accused of paraphrasing a 1933 speech by Adolf Hitler. The same month, the party launched websites to recruit child informants to spy on teachers expressing political opinions, including those in favor of LGBT rights, in the classroom. The party pushed the youths to then “denounce” the teachers anonymously online. Christian Piwarz, the culture minister in the state of Saxony, called the move a “despicable mindset of snoopery...from the times of the Nazi dictatorship or the Stasi.”

On December 7, the sexual-health charity AIDS-Hilfe Sachsen-Anhalt Nord e.V. criticized the AfD representative Hans-Thomas Tillschneider for a Facebook post that echoed Nazi-era propaganda against homosexuals by claiming that HIV sufferers were “martyrs of a disinhibited, hedonistic, hypersexualized society.”

Given the AfD’s homophobic reputation, it is perhaps surprising that 39-year-old Alice Weidel, its other co-leader, is a lesbian who lives with her female partner and children. But instead of advocating for LGBT rights, the former investment banker wants to protect gay Germans from “dangerous” Muslims whom she has called “headscarf girls, welfare-claiming knife-wielding men and other do-nothings.” The party even has a vocal LGBT group called “Alternative Homosexuals” that opposes migrants.

When questioned about her comments, Weidel has blamed the media for spreading “propaganda” and insisted to Der Tagesspiegel, a German newspaper: “I’m being credited with being involved in a supposedly homophobic party, but that's not the reality.”

Anti-LGBT sentiment appears to be spreading beyond far-right parties, too. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s replacement as leader of the ruling Christian Democratic Union is Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the party’s former general secretary. She has previously claimed that same-sex marriage could lead to the legalization of incest.

“You could argue that we live in a climate of hate speech,” says Markus Ulrich, the spokesperson for the Lesbian and Gay Federation in Germany, an influential lobbying group. While Ulrich believes that the majority of the mainstream left and center-right parties have “made their peace” with recent pro-LGBT legislation and would fight attempts to repeal it, the growing influence of far-right politicians is worrisome. “This is definitely a step towards concrete, violent action against the LGBT community,” he adds.

For now, Berlin’s sexual subcultures continue to walk in the footsteps of their pioneering forebears from the 1920s. It remains, still, a place for The Other.

At around 2:50 a.m., in the dark and pungent night club SO36 in the hipster neighborhood of Kreuzberg, Pansy, the blonde-wigged, gold-leotarded, hairy-legged host of the Miss Kotti drag-queen beauty pageant, leaned into the microphone.

“It gets so bad, sometimes it’s impossible to get out of bed. Being suicidal when you are queer is no fucking joke, and it happens far too often in this city,” she told the beer-soaked crowd. “But the one thing that keeps me going is drag. Coming to rooms like this and seeing everything right with the world.

“The only way that we get over it,” she said, to drunken shrieks of approval, “is when we come together as human beings and celebrate each other. You know what I mean?

* This article originally mischaracterized the outcome of the 1932 election.

Alice Hutton is a journalist with Der Tagesspiegel as part of The George Weidenfeld Bursary.