Abstract

This paper expands upon examinations of the flexibility–stability continuum of organizational culture in the extant literature by identifying how the four culture types of the competing values framework are associated with the emphasis on management control systems (MCS) and environmental management control systems (EMCS). By analyzing data drawn from a dyadic survey addressing both heads of management accounting and heads of sustainability or environmental management, this paper provides empirical evidence for multiple direct associations of different culture types, specifically, adhocracy, bureaucracy, clan, and market cultures, with a set of environmental and general management controls, specifically, action, cultural, personnel, and results controls. For instance, bureaucracy cultures are positively associated with action, personnel, and results controls for MCS and cultural controls for EMCS, while clan cultures are positively associated with cultural and personnel controls for MCS but negatively associated with action and results controls for EMCS. According to our findings, firms cannot transfer their emphasis on general MCS to specific EMCS because different organizational cultures are associated with MCS and EMCS in different ways. This disentanglement of organizational culture facilitates a deeper understanding of environmental controls at the organizational level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The impact of organizational culture on management control systems (MCS) has long been the subject of scientific discussion (e.g., Dent 1991; Flamholtz et al. 1985). Organizational culture includes a set of shared beliefs, values, norms, and assumptions (Anthony and Govindarajan 2007) and indirectly influences how employees perceive and address their tasks (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Organizational culture has an impact on “practically all aspects of organizational interaction as well as activities at the top management level” (Henri 2006, p. 82) and is the starting point for the design of control systems (Flamholtz 1983). The underlying values and norms affect visible artifacts such as MCS (Anthony and Govindarajan 2007) that encompass information-based routines and procedures. MCS include mechanisms that directly influence employee behavior and decisions to achieve organizational goals (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017).

Previous empirical research has confirmed the relationship between organizational culture and MCS (e.g., Bhimani 2003; Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006). According to Henri (2006), firms that emphasize flexible values (e.g., clan and adhocracy culture types) tend to use performance measures as part of MCS more than firms emphasizing stability values (e.g., bureaucratic and market culture types). Consistent with these findings, Heinicke et al. (2016) reveal that firms emphasizing flexible values also emphasize the communication of organizational values through cultural controls. Previous research has focused mostly on the flexibility–stability values of the competing values framework. Nevertheless, the competing values framework essentially interprets “a wide variety of organizational phenomena” (Cameron and Quinn 2011, p. 35). In addition to the flexibility-versus-stability continuum (structural dimension), the competing values framework differentiates between an internal or external orientation of organizational culture (focus dimension) (Cameron and Freeman 1991). The emerging four specified culture types, adhocracy, bureaucracy, clan, and market cultures, link values, beliefs, and assumptions with behaviors and strategic emphasis (e.g., cohesiveness or competitiveness and human development or market superiority) (Cameron and Freeman 1991; Cameron and Quinn 2011). A firm can have the characteristics of all four culture types simultaneously, with different characteristics being pronounced. However, in most cases, one culture type is dominant.

Due to the neglect in previous research of the second dimension, the external–internal organizational focus, the extent to which MCS reflect aspects of all four culture types has not been adequately covered, as some organizations emphasize interacting and competing with other organizations to achieve differentiation (i.e., an external focus), whereas others emphasize harmony and integration (i.e., an internal focus) (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Based on previous theoretical (e.g., Cameron and Freeman 1991; Flamholtz 1983; Ostroff et al. 2013) and empirical studies (e.g., Bhimani 2003; Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006), we assume that firms with different cultural values emphasize different levels of management control. Thus, our study extends the previous literature that is focused on the flexibility–stability dimension.

Furthermore, there is an urgent need to include environmental aspects in management control research (Asiaei et al. 2022) and its practical applications to cope with global changes at the organizational level (Florêncio et al. 2023). One of the most important global challenges in the upcoming decades is environmental change. Climate change; environmental degradation due to air, soil, and water pollution; the depletion of natural resources; and the destruction of natural habitats pose serious threats (Steffen et al. 2015). These threats must be addressed at the organizational level by widening the scope of practices, policies, procedures, and rules (Abdullah et al. 2016; Asiaei et al. 2022; Florêncio et al. 2023). The extant research shows that organizational culture is an antecedent and that management accounting associated with management control is a component of the change process that fosters organizational change toward environmental sustainability (Tipu 2022). Furthermore, “the selection of the right combination of [low carbon practices] based on […] culture” (Ambekar et al. 2019, p. 146, insertion added) reduces carbon emissions. Low-carbon practices provide information about environmental performance and waste management (Ambekar et al. 2019) and are part of environmental management control systems (EMCS). EMCS take environmental issues into account and allow “an organization to ground its future-oriented, operational and strategic management decisions on the collection and evaluation of environmental information covering all company functions and the entire value and supply chain” (Guenther et al. 2016, p. 154). Thereby, EMCS may enhance ecological sustainability within a firm and both determine environmental strategy and translate that strategy into performance (Rehman et al. 2021; Rötzel et al. 2019). However, previous studies of culture and EMCS have mostly been qualitative case studies or conceptual papers (e.g., Johnstone 2018; Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010), even though management accounting and control research on environmental issues has a history of more than 40 years, particularly in German-speaking countries (Guenther and Wagner 1993; Letmathe and Wagner 1988; Schaltegger and Sturm 1992; Strebel 1980). Events pertaining to environmental issues such as the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 1990, the establishment of DIN EN ISO 14001 in 1996, and the appearance of Al Gore’s documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” in 2007 generated widespread attention among the public.

Hartnell et al. (2011, p. 686) state that “quantitative studies that delineate the variables that influence the mechanisms through which culture influences organizational outcome help extend our knowledge about culture’s nomological network.” Furthermore, Tipu (2022) encourages future research to investigate the influence of organizational antecedents such as organizational culture on management accounting and control in the context of achieving ecological sustainability. Following these arguments and results as well as considering environmental aspects, this paper investigates two research questions:

-

1.

How is the extent of the different types of organizational culture associated with the emphasis on different types of general and environmental management controls?

-

2.

To what extent do the results of the association of organizational culture with MCS and with EMCS differ?

Thus, this study makes two contributions to the literature. First, the in-depth analysis of organizational culture following the competing values framework goes beyond the examination of the flexibility–stability continuum and investigates how the extent of the four culture types is associated with the emphasis on general MCS and ecological awareness-raising EMCS. Following Merchant and Van der Stede’s (2017) object of control framework, managers choose among four management controls—action controls, cultural controls, personnel controls, and results controls—to design their MCS and EMCS. This holistic view provides new insights because the two flexibility culture types—clan and adhocracy—and the two stability culture types—bureaucracy and market—are differently associated with management controls and environmental management controls. Second, the combination of two research streams—management control research with sustainability management and environmental accounting research—shows that all four culture types differ in their associations with emphasis on management controls or on environmental management controls. Based on survey data from a matched sample of 112 firms in which, for each firm, the head of management accounting responded to the MCS questionnaire and the head of sustainability or environmental management responded to the EMCS questionnaire, we find that the associations of organizational culture and general MCS cannot be transferred to the specific field of EMCS and vice versa. Regardless of the status of the integration of EMCS into MCS, it is recommended that the different aspects of both management systems should be recognized and applied in research and corporate practice. Thus, it is worthwhile for researchers to analyze MCS and EMCS separately if they are not fully integrated into one system in corporate practice.

In the next section, the paper discusses the underlying theoretical framework. In Sects. 3 and 4, the hypotheses are derived, and the chosen research methods are presented. Finally, the paper presents the results (Sect. 5), discusses major findings (Sect. 6), draws conclusions and describes practical implications (Sect. 7).

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Theoretical foundation

Following Flamholtz (1983), organizational culture as an important internal factor can be seen as the starting point for the design of MCS. He states that the transmission of the defined organizational culture based on the values and beliefs of a firm is conducted and reinforced by the management system.Footnote 1 Thus, the management system ought to be compatible with the organizational culture (Flamholtz 1983; Flamholtz et al. 1985). Empirical research supports this theoretical argument (e.g., Bhimani 2003; Goddard 1997). Bhimani (2003) examines how values of the organizational culture are embedded in new MCS and concludes that the success of MCS is influenced by the alignment between organizational culture and MCS. Goddard (1997) investigates the contingent relationship between organizational culture and budgetary participation and finds evidence that organizational culture has an influence on participation. While organizational culture as an anchor point for management systems (Denison 1990; Mueller 2012) conceptualizes the internal environment with its social pattern, MCS encompass the control mechanisms of a firm (Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006). However, cultural controls as a component of (environmental) management systems and organizational culture are distinct constructs that are associated with one another. Organizational culture is embodied within the organization and thus determines the actual behavior of employees (Schein 2010). It is “the deep structure of organizations” (Denison 1996, p. 654). Every organization has an organizational culture (Henri 2006), whether explicit, as managed by mechanisms (e.g., cultural controls), or implicit and accepted as a given by the management without any attempts to change it (Schein 2010). Therefore, organizational culture as a contextual factor of management controls has an indirect influence on individual or group behavior, whereas management controls represent mechanisms that directly influence behavior to achieve organizational goals (see Figure 1 in Flamholtz et al. 1985). Cultural controls are management mechanisms used to interact with employees and actively manage their behavior. They can foster the organizational culture within the firm (Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmüller 2019).

It is important that the focus of MCS and EMCS is consistent with the core values of the organization; otherwise, MCS and EMCS could have a dysfunctional effect on employees’ behavior (e.g., Akroyd and Kober 2020; Bhimani 2003; Flamholtz 1983; Markus and Pfeffer 1983; Ong et al. 2019; Sugita and Takahashi 2015), as organizational culture interacts with both management controls and environmental management controls (Heinicke et al. 2016; Länsiluoto and Järvenpää 2010; Ong et al. 2019). According to the management control literature, organizational culture is considered to be a contextual factor that affects the emphasis of MCS (Chenhall 2003, 2006; Goddard 1997; Otley 2016). Contextual factors are anchored in contingency theory, which requires an emphasis on MCS that are best suited to the external factors and internal characteristics, such as organizational culture, of the organizations in which they operate (Chenhall 2003; Otley 1980). Therefore, the assertion of contingency theory is that no distinct organizational construct (e.g., organizational culture and MCS as well as EMCS) is universally applicable in every situation. However, research on organizational culture and MCS design is sparse (Chenhall 2006; Otley 2016). Therefore, our study intends to examine the association between organizational culture as the context in which a firm operates and the extent to which MCS and EMCS are established within the firm. This study follows the congruence approachFootnote 2 of contingency theory based on selection fit (Drazin and Van de Ven 1985; Gerdin and Greve 2004; Grabner and Moers 2013) because its purpose is to explore the association between organizational culture and the emphasis on MCS and EMCS. Selection fit studies do not address how this association is linked to performance or effectiveness criteria (Chenhall 2003; Drazin and Van de Ven 1985; Gerdin and Greve 2004), as they have assumed that the firms are in equilibrium (i.e., that only high-performing firms survive) and thus that no major variations in performance can be observed.

2.2 Definition of constructs

2.2.1 Organizational culture

Organizational culture is composed of the shared values, norms, assumptions, and beliefs that influence employees in their daily routines (Schein 2010). It serves as an anchor point for management systems (Denison 1990; Mueller 2012) and thus for management controls (Flamholtz 1983). Furthermore, organizational culture affects employees’ behavior with regard to their interactions with other members of the organization and external stakeholders and thus affects practices within the firm. Moreover, organizational culture provides guidance on how to perceive and thus solve problems as well as on how to make decisions about internal and external challenges; it can foster commitment to the organization and its goals and create a group feeling among employees (Choueke and Armstrong 2000; Khazanchi et al. 2007). In summary, organizational culture is a complex system that includes numerous different aspects constituting the pattern of social life within a firm (Mueller 2012). Consequently, organizational culture should not be described with only one variable because it comprises a complex, interrelated, comprehensive, and ambiguous set of factors (Cameron and Quinn 2011).

To empirically analyze organizational culture, this study applies the competing values frameworkFootnote 3 (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983), quantifying the rather comprehensive general term of organizational culture into four specified culture types. Adhocracy cultures are based on employees’ commitment to innovation and their willingness to try new things and take risks. Loyalty is the key value of clan cultures, fostering commitment to the firm “family” and to personal ties. Bureaucracy cultures are dominated by formality and predictability to ensure stability, smooth operation, and efficiency. The achievement of goals and competitive actions are emphasized by market cultures, which have an external and results-oriented focus. The four culture types vary along a continuum based on two crossed axes—flexible versus stable organizational structure and internal versus external organizational focus—that define four quadrants (Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). Each type emphasizes different values and norms, leading to distinct organizational philosophies, strategies, and management styles (Cameron and Freeman 1991). A firm can have the characteristics of all four culture types simultaneously, with different characteristics being pronounced. Nevertheless, in most cases, one culture type is dominant and consequently stronger than the other types. The competing values framework measures both a firm’s cultural type and its cultural strength (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Consequently, it accommodates the frequent observation that every organization has its own combination of different values and cultural orientations (Schein 2010) and thus a distinct organizational culture (Lepore et al. 2018). The competing values framework is applied in this study because it is a widely accepted classification model of organizational culture. It has been used in many empirical research studies (e.g., Dubey et al. 2017; Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006; Ong et al. 2019). Moreover, it is regarded as a reliable tool for quantifying organizational culture and has been empirically derived and validated in previous research (Liu et al. 2010).

2.2.2 Management control systems and environmental management control systems

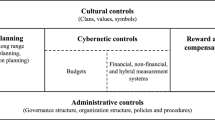

A primary function of MCS is to influence employees’ behavior in a desirable way so that they act and behave consistently with organizational goals (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017). Communication of organizational goals and highlighting areas of opportunity can eventually enable more effective management of businesses and increase goal achievement in an organization (e.g., Chenhall 2003; Merchant and Van der Stede 2017; Simons 1995). To assess the emphasis on MCS, we refer to the object of control framework by Merchant and Van der Stede (2017) as one well-known management control framework that is based on four controls—action, cultural, personnel, and results controls.

Cultural controls communicate intended organizational shared values and norms through personal communication from managers or formal mission statements to employees (e.g., a code of conduct), who are expected to act accordingly. These controls motivate and inspire employees and induce employee self-control (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017). Together with personnel controls, cultural controls are person-oriented. Personnel controls are focused mainly on the employee at an individual level, whereas cultural controls are also focused on the employees as a group. Personnel controls help to clarify the expectations of organizations and the requirements for employees (e.g., experience, knowledge) through appropriate employee selection and placement (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017).

In addition to these social types of controls that apply both direct and indirect characteristics and measures (Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmüller 2019), the object of control framework encompasses two direct types of controls (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017; Strauß and Zecher 2013): action and results controls. These two types of controls also deal with employees but do so more on an administrative and technical level than on a social level. They are also referred to as process controls (action controls) and output controls (results controls) (Sageder and Feldbauer-Durstmüller 2019). The focus of action controls is the prescription of desired actions to ensure that employees act in the interests of the organization, which is accomplished by providing direction and holding employees accountable for their actions (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017). Results controls are based on performance indicators that are used to evaluate and monitor employee output (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017).

While MCS influence organizational actors’ general practices and behaviors and shape organizational strategy and support in achieving organizational goals (Chenhall 2003; Merchant and Van der Stede 2017), EMCS enable a holistic integration of environmental topics into organizational processes and strategies as well as the interaction and incorporation of environmental strategy, environmental management, and environmental accounting into organizational practices and routines to achieve organizational environmental goals (Guenther et al. 2016; Johnstone 2018). There is a dire need for a distinct management tool that focuses on the holistic integration of environmental topics into corporate practice because environmental aspects are often misplaced or neglected by general management control frameworks (Burritt and Saka 2006; Johnstone 2018). All organizational activities have to be aligned with a holistic environmental strategy to focus and motivate all organizational actors on the path toward corporate ecological sustainability (Gond et al. 2012; Johnstone 2018). EMCS support and foster a shift toward a sustainable approach of doing business, which may further lead to improved organizational performance (Bresciani et al. 2022; Guenther et al. 2016; Henri and Journeault 2010). EMCS consist of different controls (action, cultural, personnel, and results controls) and can be defined in terms of the information-based routines and procedures that are used to influence patterns in organizational activities focusing on all environmental aspects by using the necessary environmental information, which covers every corporate function and process (Gibassier and Alcouffe 2018; Guenther et al. 2016). Thus, organizational environmental goals can be achieved with this appropriate control mechanism, namely, EMCS. A comprehensive environmental strategy that is controlled and emphasized via EMCS can expand the organizational view beyond the economic dimension.

3 Hypothesis development

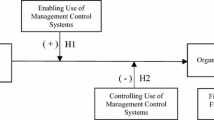

Based on the theoretical background of contingency theory, this study examines the association of the extent of the different culture types of the competing values framework and the emphasis on MCS and EMCS.Footnote 4 Gond et al. (2012) explain that MCS and sustainable control systems can be decoupled to address both organizational financial goals (via MCS) and, organizational environmental goals (via EMCS) equally. Thus, we develop separate hypotheses for MCS and EMCS, suggesting differing results. Figure 1 comprises the conceptual models for this study, one for MCS and the other for EMCS.

3.1 Adhocracy cultures, MCS, and EMCS

The core values of adhocracy cultures are external, competition-oriented, flexible, and change-oriented and include spontaneity, adaptability, responsiveness, and commitment to innovation to create pioneering initiatives, achieve growth, and acquire new resources (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). Organizations with adhocracy values are entrepreneurial firms whose managers are risk takers and visionaries. The major task of such organizations is “to foster entrepreneurship, creativity, and activity ‘on the cutting edge’” (Cameron and Quinn 2011, p. 49). The centralization of power or authority relationships is mostly absent from such firms, as teams are temporary.

Action controls “are not effective in every situation. They are feasible only when managers know what actions are (un)desirable” (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017, p. 86). In situations where spontaneity, adaptability, and responsiveness are desired and pioneering initiatives are the guiding principle (Cameron and Quinn 2011), it is not possible to know which actions are desirable (Haustein et al. 2014). Established pathways and designated actions can deter innovative processes and the elaboration and practical application of new ideas such as environmentally friendly technologies (Morsing and Oswald 2009). In addition, firms with an adhocracy culture delegate decision-making authority to subordinates and teams to enable rapid responsiveness and flexibility (Haustein et al. 2014). As a consequence, strict prescriptions of desired actions can limit spontaneity. The adoption and promotion of new innovative ideas to improve environmental sustainability and thus environmental performance require new approaches and “out-of-the-box thinking” (Bresciani et al. 2022; Pandithasekara et al. 2023). Vodonick (2018) states that the flexibility and creative nature of adhocracy cultures, which promote inherent change toward sustainability, cannot be forced into a static framework of predetermined actions that are already prescribed in every detail. Thus, general and environmental action controls are not emphasized in adhocracy cultures.

However, flexible cultures, which espouse creative values, are positively associated with cultural controls (Heinicke et al. 2016). Through the communication of core values such as commitment to innovation and technological development, the mind-set of employees in temporal, interdisciplinary teams can be adjusted, and employees can be inspired, motivated, and guided in terms of opportunity-seeking behavior (Granlund and Taipaleenmäki 2005; Haustein et al. 2014; Mundy 2010). Moreover, we assume that cultural controls play a crucial role in managing environmental issues in adhocracy cultures because managers who have vision and flexible, externally oriented values place greater emphasis on a holistic approach to environmental issues (Rotzek et al. 2018; Sugita and Takahashi 2015). If environmental topics are promoted and explained both through interpersonal communication channels and to subordinates by top management on a regular basis, the likelihood of acceptance increases. In this case, a successful application of environmental performance measures is more likely (Gond et al. 2012; Johnstone 2022). Employees are allowed to engage in spontaneous actions with fast responsiveness (Henri 2006). This creative context requires a high level of expertise because the probability of unpredictable changes in the external environment is high (Abernethy et al. 2015; Haustein et al. 2014). Thus, employees must be open to the possibility of change. Managers in firms with predominant adhocracy cultures view the change that is necessary to create an ecologically sustainable organization as a positive opportunity for growth and achievement and not as a threat to their current business model (Vodonick 2018). Consequently, general and environmental cultural controls are beneficial in adhocracy cultures in that they communicate these core environmental values.

In addition, entrepreneurial firms with decentralized power need employees who are motivated to use decision-making authority in such spontaneous situations (Campbell 2012; Haustein et al. 2014). To select capable employees, innovation-oriented organizations use personnel controls to ensure person-organization fit and acceptance of core values (Abernethy et al. 2015; Campbell 2012; Haustein et al. 2014; Stone et al. 2007). This also applies for environmental topics. If firms are committed to green activities and to reaching environmental goals, the employees themselves should promote environmental issues (Ong et al. 2019). Johnstone (2021) and Úbeda-García et al. (2022) show that employees’ individual environmental values and beliefs are important to be taken into account when a firm aims to improve its environmental performance. Hence, attitudes towards environmental topics should be a part of the personnel selection process. Moreover, possibilities for qualification in environmental topics must be provided on a regular basis to instill this motivation in relation to environmental topics (Pondeville et al. 2013; Taormina 2009; Úbeda-García et al. 2022). Thus, both general and environmental personnel controls are positively associated with adhocracy culture.

Previous studies have found that an emphasis on results controls as an evaluation tool is positively associated with innovative cultures and that innovation-oriented organizations benefit from the use of such controls (e.g., Kasurinen 2002; Wynen et al. 2014). Decentralized structures, which are present mostly in adhocracy cultures, emphasize budget plans (e.g., Merchant 1981) and performance measures (e.g., Abernethy et al. 2004). The monitoring and evaluation of performance indicators ensure that subordinates’ decisions are in accordance with organizational innovation goals, e.g., improvements in organizational ecological sustainability (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010) and can be readily compared with those of external competitors (Haustein et al. 2014). Furthermore, Johnstone (2022) reveals that environmental goals can also be achieved through budget and follow-up procedures. Therefore, monitoring and performance tracking as important parts of results controls facilitate the implementation and adaptation of environmental strategies and revisiting of the organization’s targeted results; thus, this approach is beneficial in adhocracy cultures. Based on the above considerations, we hypothesize the following for both MCS and EMCS:

H1_MCS and H1_EMCS: The extent of adhocracy cultures is negatively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental a) action controls but positively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental b) cultural controls, c) personnel controls, and d) results controls.

3.2 Bureaucracy cultures, MCS, and EMCS

Bureaucracy cultures emphasize internal, stability-oriented values such as predictability, formality, and conformity through standardized rules and policies and smooth-running operations (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). Organizations with bureaucracy-oriented values are formalized and have structured workplaces where “[p]rocedures govern what people do” (Cameron and Quinn 2011, p. 42). When managers serve as coordinators or administrators with centralized decision-making power, organizations can achieve efficiency and predictability.

Action controls can shape desirable actions through administrative constraints (e.g., by the restriction of decision-making authority) or an administrative mode of communication (e.g., by rules, policies, procedures) (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017). These prescriptions for desired actions are most suitable in stable, bureaucratic organizations (Mundy 2010). Centralized decision-making that uses administrative constraints limits decision-making authority (e.g., approval of expenditures). The performance of the desired environmental actions aimed at achieving organizational environmental goals can be emphasized and controlled via the top-down management approach (e.g., through disapproval of business trips by plane because the corporate environmental policy states that the carbon footprint of business trips should be reduced or by introducing a required material reuse quota to make processes ecologically sustainable) that characterizes bureaucracy cultures (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). A consistent framework of rules, regulations, and procedures regarding environmental topics has been proven to be efficient in such cultures (Ong et al. 2019). Consequently, general and environmental formalized rules, policies, and procedures that explain the actions for which employees are to be held accountable (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017) can be beneficial in bureaucracy cultures.

The communication of core values, purposes, and directions as well as encouragement of mutual monitoring (i.e., identifying those who deviate from organizational norms and values) through cultural values is not crucial, as compliance is achieved through standardized and formalized rules, policies, and procedures. Bureaucratic organizations are more goal-directed than value-directed organizations; thus, general cultural controls are not emphasized (Heinicke et al. 2016). However, it is important to inspire, motivate and convince employees of values related to an intended shift in corporate activities such as an environmentally sustainable business approach that seeks to have an impact in more than merely financial terms. Thus, a comprehensive alteration that requires organizational adjustments must emphasize environmental topics in organizational processes (Vodonick 2018), for example, by periodically seeking measures to reduce waste disposal and emissions. This goal can be achieved in stable cultures with cultural controls by communicating core environmental values via formalized mission statements and guidelines (Ditillo and Lisi 2016; Johnstone 2022; Ong et al. 2019) with the aim of convincing employees that an environmentally sustainable approach to business is important. The differences in hypotheses between MCS and EMCS arise because in bureaucracy cultures, MCS need clearly defined processes that are facilitated by strict, formal controls and not with cultural controls, whereas EMCS need a conviction of necessary innovations that is facilitated with cultural controls. Employees have to believe in and be convinced of the usefulness of new innovations to enable the successful implementation of a concept such as a new environmentally sustainable business approach (Vodonick 2018), whereas routine tasks and standardized, formalized procedures do not need to be inspired by a comprehensive set of underlying values; strict and formal controls are more efficient for MCS (Heinicke et al. 2016).

However, in bureaucracy cultures, the person-organization fit is crucial (Stone et al. 2007). Through personnel controls, employees are informed about the expectations of the organization, such as predictability or rule enforcement, and the technical requirements to ensure efficient, reliable, smooth-running production (Snell 1992). Moreover, the individual attitudes and beliefs of the employees regarding environmental topics are also an important part of the personnel selection process in bureaucracy cultures to ensure that firms can reach their environmental goals (Johnstone 2021; Pondeville et al. 2013; Úbeda-García et al. 2022). Possibilities for qualification in environmental areas (e.g., staff training to reduce energy consumption) have proven to be effective in terms of raising awareness of environmental topics (Taormina 2009; Úbeda-García et al. 2022). Thus, both general and environmental personnel controls are positively associated with bureaucracy cultures.

As managers’ intentions to adhere to internal rules and policies are unambiguous, the standardized actions and thus the desirable output of employees are monitored and evaluated by results controls (Snell 1992). Moreover, in bureaucracy cultures, budgets are perceived as performance evaluations and as pressure from managers to conform to firm rules (Goddard 1997). It is essential to compare standards with realized values to reach goals (Cameron and Quinn 2011). In that they accentuate smooth-running processes such as adopting and increasing energy-saving measures in the workplace and strictly following organizational regulatory frameworks, bureaucracy cultures are also results-oriented with regard to environmental goals (Johnstone 2022; Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). Based on these considerations, hypothesis H2_MCS_b and H2_EMCS_b differ:

H2_MCS_b: The extent of bureaucracy cultures is negatively associated with the emphasis on general cultural controls.

H2_EMCS_b: The extent of bureaucracy cultures is positively associated with the emphasis on environmental cultural controls.

However, the other three hypotheses regarding bureaucracy cultures are associated in the same direction for both MCS and EMCS:

H2_MCS and H2_EMCS: The extent of bureaucracy cultures is positively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental a) action controls, c) personnel controls, and d) results controls.

3.3 Clan cultures, MCS, and EMCS

Clan cultures emphasize organizational members and flexibility-oriented values such as high cohesion, morale, and communication to enable employees’ development and empowerment and the creation of social ties (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). A clan-oriented organization is characterized as an extended family with a sense of “we-ness” and recognition of the importance of individuals. The major tasks of managers in such organizations, who are seen as mentors, are “to empower employees and facilitate their participation, commitment, and loyalty” (Cameron and Quinn 2011, p. 46).

Action controls are used to empower employees to participate in decisions and to provide organizational direction. Holding employees accountable for their actions ensures consistency with the core values of morale and individual development (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017). Akroyd and Kober (2020) confirm this statement and show that the use of operational manuals, which are associated with regular manager contact, should contain policies and procedures aimed at ensuring the continuation and spread of the family feeling. In this sense, action controls support and reinforce clan cultures. Because of the high level of employee involvement and their loyalty to one another, managers discuss relevant work steps with employees and provide them with information regarding the achievement of organizational goals. In a collaborative culture such as a clan culture, employees are focused on person-oriented benefits such as personnel development and empowerment, career options, and job security (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Environment-related actions are perceived as less important if they are not tied to person-oriented benefits (Deegan 2017; Vodonick 2018). The focus on ecological issues must be aligned with and integrated into person-oriented benefits to have the desired effects within the scope of EMCS. Nevertheless, the integration of person-oriented benefits into a comprehensive ecological context has not yet been fully established in corporate practice in most firms (Deegan 2017). Thus, environmental action controls are negatively associated with clan cultures. The differences between the hypotheses for MCS and EMCS are due to the fact that employees in clan cultures perceive person-oriented benefits as more important than ecological issues (Cameron and Quinn 2011).

Heinicke et al. (2016) state that cultural controls (in particular belief controlsFootnote 5) are key controls for flexible, value-oriented organizations. Cultural controls define and communicate the core values of cohesion, participation, and morale through open and lateral channels of communication (Henri 2006). Employees must be empowered by an organizational vision and mission statement comprising commonly shared values and collective collaboration (Cameron and Quinn 2011) to be convinced of the importance of the organization’s efforts. Thus, cultural controls are the central component of the commitment blueprintFootnote 6 for the creation of an emotional bond between employees and the organization (Akroyd and Kober 2020). Moreover, shared values and collective collaboration are distinct characteristics of clan cultures that may enable organizational change toward sustainability (Vodonick 2018). Employees must perceive environmental issues as important (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010; Úbeda-García et al. 2022). If the majority of employees are convinced of the importance of the organization’s environmental efforts, teamwork, coworker support, and implicit group pressure will help to align the employees who are not initially convinced (Taormina 2009). Thus, general and environmental cultural controls are positively associated with clan cultures.

Based on the core value of high commitment, the selection of new employees through personnel controls—and thus their identification with the organization—is crucial (Akroyd and Kober 2020). Management considers the person-organization fit that constitutes the alignment between an applicant’s values and an organization’s values (Akroyd and Kober 2020; O'Connor 1995; Stone et al. 2007). Employees identify with the organization (in particular with the firm as a “family”) and subscribe to its values. Reaching a common understanding of and commitment to environmental topics is crucial; thus, a person-organization fit is required (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010; Pondeville et al. 2013; Úbeda-García et al. 2022). For example, job candidates who reject the importance of ecological sustainability may not contribute to the achievement of organizational environmental goals (Johnstone 2018). Both general and environmental personnel controls are essential in clan cultures.

An emphasis on results controls in the monitoring and evaluation of performance and mostly hierarchical communication between managers and subordinates contradicts the management style of clan cultural organizations, where core values are created and enforced by social ties in addition to the participation, commitment, and loyalty of employees (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Henri 2006). Akroyd and Kober (2020) confirm that managers in cultures in which employees are committed and emotionally connected to the firm are reluctant to introduce bureaucratic controls such as budgets and job descriptions because they believe that doing so would impact the family feeling negatively, in which context engagement, attachment, and identification are core values of the organizational culture. Employees can be implicitly controlled through personal relationships and group thinking, and strict results controls can diminish the trust of the group. Furthermore, comparison with competitors by hard indicators is not emphasized because clan cultural organizations are internal and person-oriented. Thus, the emphasis on results controls is also insufficient to achieve an organization’s environmental goals when managers and employees are not convinced of the importance of an ecological, sustainable business approach (Vodonick 2018). Thus, both general and environmental results controls are not emphasized in clan culture. Based on these considerations, hypothesis H3_MCS_a and H3_EMCS_a differ:

H3_MCS_a: The extent of clan cultures is positively associated with the emphasis on general action controls.

H3_EMCS_a: The extent of clan cultures is negatively associated with the emphasis on environmental action controls.

However, the other three hypotheses for clan cultures are associated in the same direction for MCS and EMCS:

H3_MCS and H3_EMCS: The extent of clan cultures is positively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental b) cultural controls and c) personnel controls; however, these cultures are negatively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental d) results controls.

3.4 Market cultures, MCS, and EMCS

Market cultures emphasize external, stability-oriented values such as customer focus, competitiveness, and productivity (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). Organizations with market cultural values are results-oriented workplaces in which competitive actions, goal achievement, production, and market results are crucial. The major task of managers, who are seen as tough producers and competitors, is “to drive the organization toward productivity, results, and profit” (Cameron and Quinn 2011, p. 45).

These goal-directed, market-oriented organizations require a prescription of desirable actions and administrative modes of communication to encourage adequate behavior (e.g., Jordão et al. 2014; Mundy 2010; Verbeeten and Speklé 2015). Employees are accountable if goals are not achieved, and they must discuss the next relevant steps with their managers. Employees should follow rules and procedures to achieve organizational goals such as profitability or customer satisfaction; thus, action controls are emphasized in market cultures.

Due to an external focus on productivity, results, and legislation, cultural and personnel controls seem to be ineffective in market cultures. Employees are not personally involved, and personality traits focus more on the rapid adoption of new trends set by the market, competitiveness and self-reliance than on soft factors such as values. Therefore, the communication of and adherence to shared values are not emphasized.

Employees are evaluated by performance indicators that are monitored and assessed by managers. This outcome orientation fosters an emphasis on results controls for the purpose of controlling costs in preparing decisions (Baird et al. 2004) and providing feedback to employees when deviations from results occur.

However, in terms of environmental sustainability, organizations with a market culture focus on measures to cut costs, improve efficiency and maximize output. Such organizations understand ecological sustainability in terms of meeting legal and market requirements and reducing input (e.g., materials and energy). Increasing market share and thus sales is more important than encouraging employee innovation to seek alternative solutions and facilitate change toward ecological sustainability (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010; Vodonick 2018). One reason is that firms with predominant market cultures are inclined to avoid major changes in their approach to conducting business and consider environmental issues to be of only secondary importance, which prevents the adoption of a truly ecological sustainable business model (e.g., Mårtensson and Westerberg 2016; Paulraj 2009). The adoption of organizational ecological initiatives depends on market conditions. Market cultures adopt ecological sustainable measures only when competitors are successful with such initiatives (e.g., by increasing customer satisfaction and thus gaining market share) or when external incentives and pressures (e.g., by subsidies, legislation, or other stakeholder interventions) occur (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). Based on these considerations, the following hypotheses differ between MCS and EMCS:

H4_MCS_a and H4_MCS_d: The extent of market cultures is positively associated with the emphasis on general action controls and general results controls.

H4_EMCS_a and H4_EMCS_d: The extent of market cultures is negatively associated with the emphasis on environmental action controls and environmental results controls.

However, the remaining two hypotheses for market cultures are associated in the same direction for MCS and EMCS:

H4_MCS and H4_EMCS: The extent of market cultures is negatively associated with the emphasis on general and environmental b) cultural controls and c) personnel controls.

4 Research methods

4.1 Data collection and sample

The empirical data for this dyadic study were collected through two structured questionnaires following the total design method of Dillman et al. (2014). Based on net sales and availability in the AMADEUS database, the survey population comprises the 3,000 largest German private firms from the trade, production, and services industries (see Table 1). Following the exclusion of firms from the non-profit sector and the financial industry and of subsidiaries of other sample firms, the target sample consisted of 2285 firms. This setting was chosen because large firms are more likely to have sophisticated MCS and more available resources for an environmental or sustainability department that can emphasize EMCS.

In February 2015, the survey began by contacting all firms by mail and phone to arouse initial interest and to identify the appropriate contact person. Ninety-nine firms could not be reached as a result of mergers or closures and were removed from the sample. Due to the dyadic study design, the final 2186 firms received two personally addressed and signed packages. The MCS questionnaire with a specific cover letter was delivered to the chief financial officer (CFO) or head of management accounting as key informants on MCS, and the EMCS questionnaire with the other cover letter was delivered to the head of environmental or sustainability management as the organization’s expert on EMCS. Each respondent also received an addressed and stamped return envelope. As incentives, the respondents were offered an evaluation report and an invitation to a workshop in which the survey results would be presented. In August 2015 and February 2016, two follow-up mailings were conducted to increase the response rate.

The dyadic design ensures that the most appropriate respondent is contacted to examine the conceptual models. Different corporate executives with different responsibilities have different perspectives on and insights into the organization (Linnenluecke et al. 2009), and thus, a dual source for the MCS and the EMCS data reduces the bias of selective reporting (Iacovou et al. 2009). The CFO or the head of management accounting is the most appropriate respondent to assess the general MCS questionnaire but not the specific EMCS questionnaire, and the head of environmental or sustainability management is the appropriate respondent for the EMCS questionnaire but not for the MCS questionnaire. The wording of the items of the MCS questionnaire was slightly adjusted for the specific environmental context of the EMCS questionnaire. Thus, the dyadic study design enables a more detailed view and better conceptualization (Mahapatra et al. 2010) of the constructs of MCS and EMCS, allowing for a holistic comparison.

Our study seeks to analyze the general organizational culture and not the subcultures of different departments, such as a distinct environmental or sustainability culture that is present only in a certain department. Thus, the organizational culture items were included only in the MCS questionnaire because organizational culture is in most cases evaluated and potentially adjusted by general corporate management (Schein 2010) and not by the head of environmental or sustainability management, following the integrational perspective of organizational culture (a firm-wide common understanding among employees and managers about a set of shared assumptions, values and beliefs) (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010).

In total, responses were received for 260 MCS questionnaires (response rate of 11.9%) and 301 EMCS questionnaires (response rate of 13.8%). Prior management surveys on general and environmental management topics (e.g., Heinicke et al. 2016; Sugita and Takahashi 2015; Widener 2004) have reported comparable response rates. This paper, as a dyadic study, is based on data gathered from the two separate experts of a firm. Thus, a combined dataset was generated that contained the items from both questionnaires for all firms. The matched samples consisted of 112 responses for each questionnaire, which corresponded to a response rateFootnote 7 of 5.12%.Footnote 8 The 112 MCS respondents (EMCS respondents)Footnote 9 had an average tenure of 13.26 (15.69) years within their firms, and they had worked in their present jobs for an average of 6.23 (7.61) years. Moreover, the majority of the investigated firms had implemented a certified environmental management system (EMS) and consequently were required to have environmental objectives, as a certified EMS installs a corporate process of continuous improvement to achieve corporate environmental goals (DIN EN ISO 14001 2015).Footnote 10

As the response rates to management sample surveys have decreased in recent decades, obtaining an adequate dyadic response rate is even more difficult, and low response rates are therefore not uncommon (Nuhn et al. 2019). However, Van der Stede et al. (2006, p. 472) state that “[e]ven when response rates are low, the results are still generalizable if there is low non-response bias.” The “Appendix” shows that nonresponse bias is not a major issue for our study.

4.2 Measurement of constructs

The data were collected with two questionnaires that were based on well-established and validated items from previous research and were pretested and discussed with twelve experts (academics and practitioners from different industries and countries) and revised if necessary. All survey items were based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = neither nor; 7 = strongly agree). They were assessed by the respondents on the basis of an average of the last three years to reflect data for a longer period of time. Therefore, the items assess the medium-term organizational development of the firms and do not depict an instant view or a short-term phenomenon.

Like most survey studies, this study may be subject to common method variance (CMV); however, several actions were taken to reduce this possibility. First, CMV was proactively addressed by procedural remedies during survey development by devoting great attention and work to the questionnaire design. The respondents’ anonymity and confidentiality were ensured. They were also informed that honesty would aid the survey and that there were no right or wrong answers (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Speklé and Widener 2018). Moreover, the headlines were encoded to conceal the theoretical constructs behind each section and to avoid guiding the respondents with a cognitive map; thus, the question order was carefully chosen (Chang et al. 2010). Second, the dyadic design of this study reduced the effect of CMV (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Spector 2006) for the EMCS model, as organizational culture and EMCS were assessed by two respondents from each firm. Third, Harman’s (1976) single-factor test revealed that only 31.5% (31.7%) of the total variance was explained by one factor in the MCS (EMCS) model.

Extent of organizational culture. This construct is based on the competing values framework (Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). The four types of culture—adhocracy, bureaucracy, clan, and market—were measured using an adaption of Cameron and Freeman’s (1991) initial measurement (Lukas et al. 2013). The respondents were asked to rate their perceptions of the specific cultural profile of their firms by assessing four items for each culture type (see Panel A of Table 2). In this study, the four culture types were not aggregated to a flexible or stable culture, as has been done in previous studies (e.g., Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006). The chosen approach allowed for a more detailed investigation, as previous studies have proposed (Johnstone 2018; Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010), as both the type of culture and the culture strength were measured. Due to a sample size of n = 112, the culture types were treated as manifest variables using factor scoresFootnote 11 (Widener 2004, 2007). This technique is used mainly when working with small sample sizes because it reduces the number of parameters that must be estimated (e.g., see De Ruyter and Wetzels 1999; Widener 2004, 2007; Van der Kolk et al. 2018).

Emphasis on MCS and EMCS. This study distinguishes four types of controls—action, cultural, personnel, and results controls. To measure the controls, items from validated MCS instruments were used, and their wording was slightly adjusted for the specific context of EMCS. This step resulted in two sets of items: one for MCS with heads of management accounting or CFOs as respondents and one for EMCS with heads of sustainability or environmental management as respondents (see Panels B and C of Table 2). Action controls measure the action accountability of employees, the prescription and communication of superiors about directions, and personal limitations. Based on Jaworski and MacInnis’s (1989) prior operationalization of behavioral controls, three items from Goebel and Weißenberger (2017) and two items of Hutzschenreuter (2009) were used. The construct of cultural controls was measured by four items from Widener (2007) that emphasize organizational belief controls, including the mission statement and the communication of core values to the workforce (Merchant and Van der Stede 2017; Simons 1995). Personnel controls capture the selection and placement of employees. The three items used were based on the input controls of Snell (1992) and the measurement of Goebel and Weißenberger (2017). Results controls comprise the monitoring and evaluation of critical performance indicators by managers. This construct was measured with four items that were labeled output controls by Jaworski and MacInnis (1989) and later adapted by Goebel and Weißenberger (2017).

Control variables. The influence of three firm characteristics—industry, profitability, and organizational size—were investigated as control variables. These variables have been identified as important contingent factors for an emphasis on MCS and EMCS (Chenhall 2003). Industry was coded as a dummy variable to differentiate between manufacturing (= 1) and other industries (= 0). To measure profitability, the three-year average of archival return on assets was used. Organizational size was measured by a three-year average of archival net sales, total assets, and employee number. All size variables were transformed using the logarithm (log) to account for outliers and nonlinear effects.

4.3 Data analysis

To test the two conceptual models, structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to enable the simultaneous examination of the relationships between multiple independent and dependent variables. Moreover, SEM can operate with both manifest and latent unobserved constructs and estimate entire (more holistic) models. Furthermore, the measurement model and the structural model are estimated simultaneously (Byrne 2010; Kline 2011). These issues are crucial for the study because four independent variables (adhocracy, bureaucracy, clan, and market culture) and four dependent variables (action, cultural, personnel, and results control) were investigated, resulting in 16 path relationships estimated simultaneously. Furthermore, various control variables such as industry, profitability, and organizational size were included in our model and examined in additional analyses. Thus, an SEM approach and, in particular, AMOS 25.0 software with a maximum likelihood estimation approachFootnote 12 were chosen to analyze the empirical data. The two conceptual models were estimated in two stages: estimation of measurement and structural modeling (Kline 2011).

5 Results

5.1 Measurement model

The unreportedFootnote 13 exploratory factor analysisFootnote 14 showed that all constructs were unidimensional and above the recommended thresholds.Footnote 15 To assess the measurement models, all items of the reflective constructs were reviewed with regard to theoretical and actual scale range, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation), factor loadings, and reliability measures (see Panels A, B, and C of Table 2). When the item reliability was examined, only one item of the construct adhocracy culture had an individual item reliability that was slightly below the common threshold of 0.4 (Bagozzi and Baumgartner 1994). Nevertheless, based on theoretical considerations, this item was retained in the measurement.Footnote 16 All other measures were above the common threshold. All standardized factor loadings were significant, with values greater than 0.625. The reliability of each construct was satisfactory; as all Cronbach’s alpha and all composite reliability measures exceeded the common threshold of 0.70 (Nunnally 1978; Bagozzi and Yi 1988). Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded the commonly recommended threshold of 0.5 for each construct (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

The discriminant validity of the measurement models was tested using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion. Panels A and B of Table 3 present the correlation matrix of the MCS and EMCS constructs and of the control variables and shows the square root of the AVE as the diagonal element. The square root of AVE for each construct exceeded the correlation with any other construct, which demonstrates adequate discriminant validity.

Furthermore, the results of the correlation matrix showed that all controls of MCS and EMCS were significantly positively correlated among one another (p < 0.05),Footnote 17 which supports previous findings (e.g., Heinicke et al. 2016; Widener 2007), whereas the culture types revealed four significantly positive correlations (p < 0.05) (between adhocracy and clan cultures and between market cultures and any other culture type) and two non-significantly negative correlations (bureaucracy cultures and flexible cultures—adhocracy and clan cultures). Furthermore, the correlation between culture type and MCS was always positive and mostly significant. The correlations between culture type and EMCS were mostly non-significant but positive. However, clan cultures were significantly negatively correlated with results controls (p < 0.05). Moreover, only bureaucracy cultures and cultural controls (p < 0.01) were significantly positively correlated. Regarding the control variables, size was positively correlated with all management and environmental controls. The manufacturing industry was positively correlated with adhocracy cultures and had a higher emphasis on environmental cultural controls (i.e., positive correlation, p < 0.05). Profitability was positively correlated with adhocracy and clan cultures (p < 0.05).

5.2 Structural equation model

Following similar MCS studies, this study uses well-established goodness-of-fit indices to assess the overall model fit (e.g., Heinicke et al. 2016; Van der Kolk et al. 2018).Footnote 18 All fit statistics conform to the generally accepted thresholds (e.g., Kline 2011), which indicates that both base models have an acceptable fit. Table 4 presents the results of the SEM.Footnote 19

As expected, the results show that MCS and EMCS are not always associated in the same way with the different organizational culture types. In 10 of 16 associations, the significance of the associations with MCS and EMCS differed.

The MCS model represents the associations of the organizational culture types with the four management controls. The results show a significant and positive association between adhocracy cultures and the emphasis on cultural controls (H1_MCS_b; coefficient = 0.291, p < 0.05), personnel controls (H1_MCS_c; coefficient = 0.491, p < 0.01), and results controls (H1_MCS_d; coefficient = 0.344, p < 0.05), which partially supports H1_MCS. H2_MCS is partially supported as well, bureaucracy cultures are significantly and positively associated with the emphasis on action controls (H2_MCS_a; coefficient = 0.269, p < 0.05), personnel controls (H2_MCS_c; coefficient = 0.334, p < 0.01), and results controls (H2_MCS_d; coefficient = 0.186, p < 0.1). Regarding the association of clan cultures with management controls, clan cultures are significantly and positively associated with the emphasis on cultural controls (H3_MCS_b; coefficient = 0.246, p < 0.05) and personnel controls (H3_MCS_c; coefficient = 0.172, p < 0.1), which partially supports H3_MCS. Market cultures are significantly and positively related to the emphasis on action controls (H4_MCS_a; coefficient = 0.213, p < 0.1), which partially supports H4_MCS.

The EMCS model comprises the relationship between the organizational culture types and the environmental controls. The results show a significant and positive association between adhocracy cultures and the emphasis on cultural controls (H1_EMCS_b; coefficient = 0.259, p < 0.1) and results controls (H1_EMCS_d; coefficient = 0.274, p < 0.05), which partially supports H1_EMCS. Bureaucracy cultures are significantly and positively associated with the emphasis on cultural controls (H2_EMCS_b; coefficient = 0.274, p < 0.05), which partially supports H2_EMCS. As expected, clan cultures are significantly and negatively related to the emphasis on results controls (H3_EMCS_d; coefficient = − 0.337, p < 0.05) as well as action controls (H3_EMCS_a; coefficient = − 0.277, p < 0.05), which partially supports H3_EMCS. H4_EMCS is not supported for EMCS.

In summary, Fig. 2 illustrates the associations with the emphasis on MCS and EMCS for the four quadrants of the competing values framework.

5.3 Robustness and additional tests

To test the results for robustness, context factors as control variables were included in the base models (see Table 5 for MCS and Table 6 for EMCS). We included each control variable separately in the base model to better show the effects of each one.Footnote 20 For MCS, model A controlled for industry, model B for profitability, and model C for organizational size. For EMCS, model G controlled for industry, model H for profitability, and model I for organizational size. The significant relationships remained qualitatively unchanged.Footnote 21 Thus, the robustness tests showed that the associations between the culture type and the emphasis on MCS and EMCS were robust for industry, profitability, and organizational size.Footnote 22

This study examines the emphasis on management and environmental management controls as dependent variables. Thus, it was assumed that firms are at equilibrium (Chenhall 2003) (i.e., that only high-performing firms survive) and thus that no major variations in performance could be observed. Therefore, the analysis followed the selection fit approach of contingency theory (Gerdin and Greve 2004). However, to examine the adequacy of the selection fit of organizational culture with MCS and EMCS, we added dependent variables to test our conceptual models. For MCS, we added perceived organizational performance (model D), archival organizational performance (model E) and effectiveness of strategic planning (model F). For EMCS, we added archival organizational performance (model J) and perceived environmental performance (model K). Perceived organizational performance was measured as a latent variable comprising four items—return on assets, return on sales, cash flow return on assets, and cash flow return on sales of a firm compared to the industry average over a period of three years—informed by Hamann et al. (2013) based on the well-established measurement of Gupta and Govindarajan (1984) and Govindarajan (1988). Archival organizational performance was measured as a latent variable based on archival return on sales, return on assets, and cash flow return on assets (each arithmetic mean over three years based on the AMADEUS database). The effectiveness of strategic planning was measured based on Elbanna (2008) by eight items, such as the effectiveness of strategic planning in increasing the achievement of organizational objectives, developing a sustainable competitive position, building a performance culture among subordinates or developing a shared vision for the organization and capturing different effects and strategic capabilities of the firm. Perceived environmental performance was measured as a latent variable of five items—total direct and indirect energy consumption, total water withdrawal, total CO2 and CO2 equivalent emissions, total amount of waste produced, and total amount of hazardous waste produced by a firm—compared to the industry average over a period of three years based on Trumpp et al. (2015).

When the three additional outcome variables were included in the MCS model, all significant associations remained constant, and there were no significant associations between the four controls and the three outcome variables of the firm.Footnote 23 These empirical findings support the theoretical choice of the selection fit approach of contingency theory. Selection fit assumes that firms are in equilibrium, where no major variation in performance can be observed. This assumption is based on the natural selection process, where fit is the result of adaptation, which ensures that only the best-performing firms survive (Darzin and Van der Ven 1985; Gerdin and Greve 2004). Furthermore, organizational performance such as profitability seemed to be “influenced by numerous other conceptual and structural variables that may be difficult to control for” (Guenther and Heinicke 2019, p. 5). The addition of archival organizational performance and perceived environmental performance as dependent variables to the EMCS model did not change the significant associations between organizational culture and EMCS. The results reveal a significant positive association of environmental cultural controls with archival organizational performance and perceived environmental performance, confirming Ditillo and Lisi (2016) and Ong et al. (2019) in finding that a shared vision and inspired employees are crucial in facilitating and enhancing environmental performance. However, we found no significant associations with the other three controls, which may be explained by the time needed to establish and enhance environmental performance.

As an additional robustness test, bootstrapping (1,000 samples with replacement) was performed. The unreported resultsFootnote 24 showed that the inferences remained qualitatively unchanged (except that the path of clan culture with personnel controls for the MCS model was no longer significant (p > 0.1), whereas the path adhocracy culture with personnel controls for EMCS became significant (p < 0.1)).

6 Discussion

Organizational culture is often seen as an omnipresent firm characteristic (Chenhall 2003; Markus and Pfeffer 1983) associated with the emphasis on MCS and EMCS. Previous empirical management control research has supported this statement (e.g., Bhimani 2003; Heinicke et al. 2016; Henri 2006), whereas organizational culture has mostly been examined on a rather limiting flexibility–stability continuum. To gain a deeper understanding of the theoretical rationales, this study breaks down the flexibility–stability continuum by investigating the association between the extent of different culture types of the competing values framework and the emphasis on different types of general management controls and environmental management controls (research question 1). Our study confirms theoretical analyses (e.g., Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010) and expands upon existing empirical results (e.g., Akroyd and Kober 2020; Heinicke et al. 2016, Henri 2006, Ong et al. 2019). Furthermore, the study offers empirical evidence that firms with different types of culture are differently associated with emphases on different general management controls and specific environmental management controls.

Regarding MCS, firms with adhocracy cultures emphasize cultural, personnel, and results controls, whereas firms with clan cultures emphasize only person-oriented controls, namely, cultural and personnel controls. Both culture types are based on flexible values that motivate and inspire employees by formally communicating core values with the organizations’ beliefs. The difference is that clan cultures focus on the development and empowerment of employees (internal focus), whereas adhocracy cultures search for new resources and innovations (external focus) (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). Our findings provide the insight that cultural controls are also an integrating mechanism in larger, flexibility-oriented firms, as Heinicke et al. (2016) find for medium-sized firms. Therefore, the person-organization fit, which is achieved through the suitable selection and placement of employees (i.e., personnel controls), is crucial to ensure that the organization and its employees share similar collaborative or creative values in both culture types (Akroyd and Kober 2020). However, differences are observable regarding results controls. In addition to flexible values, adhocracy cultures are more externally focused and competition oriented; thus, the evaluation and monitoring of clear and measurable performance indicators that support the development of effective and efficient work processes are crucial (Wynen et al. 2014). By investigating both flexible culture types, this study shows that results controls are emphasized by adhocracy cultures, whereas internally oriented clan cultures emphasize only person-oriented controls to foster internal communication and ties.

At the other end of the flexibility–stability continuum, stability is featured by bureaucracy and market cultures. Both stable culture types emphasize action controls that prescribe desirable actions for their employees. Empowering employees while holding them accountable for their actions through administrative constraints (e.g., restriction of decision-making authority) or administrative modes of communication (e.g., rules, policies, procedures) ensures predictability and conformity (Cameron and Quinn 2011; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983). However, the analysis of both stability-oriented culture types shows that personnel and results controls are emphasized only in bureaucracy cultures.

Firms with bureaucracy cultures also have an internal focus, as clan cultures do. Both internal-oriented culture types emphasize the suitable selection and placement of employees. However, stability values are more compatible with results controls (i.e., the monitoring of performance indicators) than with cultural controls because bureaucracy cultures are associated with clear procedures that govern employees’ work, whereas clan cultures are associated with human relations for which performance indicators are less easily defined. We expand upon the work of Henri (2006) by breaking down the flexibility–stability continuum along the external versus internal dimension. Our study indicates an emphasis on results controls for both adhocracy cultures and bureaucracy cultures. However, the two external competition-oriented culture types, adhocracy and market cultures, emphasize completely different MCS.

For EMCS, firms with adhocracy cultures emphasize cultural and results controls, whereas firms with clan cultures are negatively associated with action and results controls. Both cultures are flexible; however, their focus on the internal–external continuum of the competing values framework differs. The goals of personnel development and the interests of the internal social network must be emphasized because clan cultures focus on human relations (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Our findings support this argument by indicating that environmental goals and activities are not managed by formal controls. Thus, more emphasis on clan cultures is associated with less emphasis on action and results controls because strict, formal controls do not support personnel ties and employee loyalty in clan cultures (Ong et al. 2019). Hence, social group pressure, employees’ intrinsic motivation for collective success, group thinking, consensus reaching, and informal processes are implicit control mechanisms (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). Nevertheless, the results show that adhocracy cultures emphasize cultural controls such as value and belief systems to communicate environmental values and norms that inspire and motivate employees for strategic change in pursuit of ecological sustainability (Marginson 2002). Johnstone (2022) confirms this finding by highlighting the fact that interpersonal communication channels (e. g., communication through top managers) foster employees’ commitment to the achievement of environmental goals and promote awareness of environmental management systems. Furthermore, she suggests that environmental goals can also be achieved through budget and performance measures. The positive association of environmental results controls with externally oriented adhocracy cultures supports Johnstone’s (2022) suggestion and indicates that feedback loops, monitoring, performance tracking, and benchmarking with competitors are crucial in the achievement of environmental goals. Asiaei et al. (2022) find similar results by showing that environmentally oriented firms associated with creativity and the commitment of employees to green innovation (green human capital as part of green intellectual capitalFootnote 25) use environment-related key performance indicators and focus on the identification, estimation, and allocation of environment-related costs.

At the other end of the flexibility–stability continuum, firms with bureaucracy cultures emphasize cultural controls, whereas firms with market cultures are not associated with any of the four environmental controls. Firms with market cultures likely operate in highly competitive markets (Gond et al. 2012) and do not focus on environmental topics except when their competitors are successful with environmental initiatives or there is consumer demand for it. Such firms react only to market conditions and stakeholder interests expressed by such means as consumer behavior. Such firms tend to apply a compliance-driven sustainability strategy (Gond et al. 2012). As a consequence, environmental topics are addressed only if there is demand or stakeholder pressure (Abdel-Maksoud et al. 2021; Nishitani et al. 2021), and if so, environmental activities are often limited to resource optimization and output maximization. Furthermore, the stakeholder pressure of firms with a dominant market culture may not be focused on environmental topics (Pondeville et al. 2013). These firms tend to merely meet environmental legal requirements rather than engaging in ecological improvement or innovation (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). In bureaucracy cultures, ecological issues are promoted through cultural controls that communicate the new environmental values that inspire and motivate employees and steer their actions in the right direction toward more sustainable procedures (Johnstone 2022). Especially in centralized firms with top-down management, organizational change can be efficiently engineered by management via the organizational value system.